Guest post by author Mike Robinson

“Back then, with the visions, most of the time I was convinced I’d lost it. There were other times, though, where I thought I was mainlining the secret truth to the universe.” — Rust Cohle, True Detective

Behind the wide facade of Speculative Fiction twist the hedge-mazes of fantasy, brood the catacombs of horror and gaze the far-seeing floors of science fiction. Among them, between them, are the closets and crawlspaces of the niche, one of which — a relatively bigger one — is the place of Weird Fiction, a dark storage of many souvenirs from fantasy, horror and science fiction, though dusted with its own special charms.

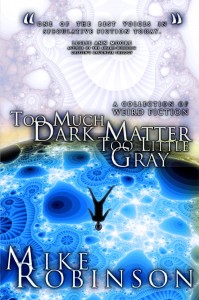

The former subtitle for my new book, Too Much Dark Matter, Too Little Gray: A Collection of Weird Fiction was actually, A Collection of Speculative Fiction. As one prone to appreciate sprawling ambiguity, to resist specific categorization, it’s a little ironic that I wanted to specify further. But there was a reason for that, besides the stodginess of “speculative”, which has none of the zany, fluid charisma of “weird”.

While using “weird” may sound like a proud judgment, a literary outcast chest-thumping his identity as such, it’s more a direct homage to the tradition of Ambrose Bierce, Robert Chambers, H.P. Lovecraft and many others. Going further, it’s an accurate classification given my vision of Weird Fiction, a subgenre that, perhaps more consciously than other fields of speculative fiction, stirs together elements of the metaphysical, cosmological and horrific to grimly honor the Big Questions, remind us of our insurmountable ignorance, to pin down our squirming selves into our rightful position in the child’s seat, to whisper, maybe in some alien, mud-packed voice, that, hey, the world slippery and you won’t ever, ever catch it. The world, in short, is weird.

And past all the horror, the strangeness, that to me is a nourishing thought. Let me explain.

The moment I cemented my decision to not pursue an M.F.A (or any academic training) in writing is vivid. While enrolled at Otis College of Art & Design, I found in my mailbox a little perfect-bound literary booklet featuring work by the graduate students in fiction. I flipped it open to a random story. After wading cautiously into the second paragraph of a painful scrutiny of eyebrow-plucking, I was done. Other entries weren’t much better. Too many of them seemed concerned with stereotypical, high-literary minutia, unfortunately the focus and baffling preference of innumerable professors, awards, journals, and workshops (cough-Iowa-cough).

Personally, I have little interest in quaint journalistic accounts of Malaysian transvestite violinists at the turn of the century (yes, I made that up), or the endless slew of aptly-termed “McFiction” featuring some cocky narrator coming of age amongst his or her overfed, dysfunctional family. No, I prefer going head-on at the Big Questions, going at them, as George Carlin might say, with no less than a sledgehammer. Give me ballsy confrontations with Life, Death, the Cosmos, with Existence, with God.

In their noble attempts at social redemption and inclusion, many contemporary teachers of literature treat writings in the framework of their political significance. To me, though, such attempts seem to me nothing more than new forms of division. It is looking at the grains and forgetting the shore. Does the world really need a Marxist reading of Huckleberry Finn, complete with ten-dollar jargon? Academics are on the lookout for the “next best thing”, the new trend in analysis, the new prism through which to see literary works of yesterday and today. I say: what about our shared heritage? Our shared — and uncertain — future? Not as any one ethnicity, gender, party, or faction, but as an entire civilization. A species. A collective piece of this vast Universe.

Of course, much of this material is studied, and much of it is exhaustively considered and written about. Enter Weird Fiction!

As any fellow devotee will know, H.P. Lovecraft — arguably the most esteemed and influential practitioner of the genre — cleaned out the catacombs with his pen, defying tropes of ghosts and vampires and expanding imaginations with interconnected tales of ancient civilizations antedating our own, of towering alien-gods, of unseen dimensions and humanity’s sanity-shattering smallness in an inexplicable cosmos. All this made more impressive by the fact that he wrote in the 1920s, when so much of that stuff was barely on anyone’s speculative radar, including scientists’. His unknowns are truly Unknown, and will forever elude explanation.

Certainly Lovecraft’s work has failings, failings probably more surface-level than those of other lauded authors. He was well aware of his own wooden dialogue (hence, quotation marks are scarce in his pages) and his prose sometimes gushes into the purple. Nevertheless, his voice, with its richly archaic, darkly celebratory cadence, stands alone, and will survive as long as we’re unsure what lurks “out there”.

Sadly, Lovecraft, and especially his “Cthulu” mythos, have become somewhat franchised, relegated to corners of the market generally aimed at Dungeons and Dragons fans, horror enthusiasts, and nihilistic young adults sporting black fingernails and lipstick. It is a wide “cult following”, but nonetheless a cult following. Although some scholars have acknowledged his importance, many see him as a troublesome bridge from Poe to Stephen King. It is this identity that has, I’m sure, dissuaded many from giving him a serious go. “Lovecraft? Oh, no, I don’t like that horror stuff.”

But back up. Here we come back to the question of Weird Fiction itself, because I don’t necessarily consider the canon, or Lovecraft’s work, “horror”. Certainly there are horrific elements in his work, and his career does include several standard supernatural yarns. But in his treatment of cosmic mysteries, and the shadowed realms of prehistory, his is more a prying curious eye, forcing us to consider those Big Questions, to ponder notions of, and issues with, the likes of religion, biology, cosmology, archaeology, and psychology. He sets you on the outside looking in, a contrast to being in and looking further in to the point of navel-gazing. This exercise of outside-looking-in, one I believe most writers of fiction should undertake, helps in a kind of rounding out of thought.

No matter the genre in which one writes, I believe the best, most poignant stories have at least an undercurrent of this “larger awareness”, a perception conveying authority and wisdom. So many stories feel constricted by their own world, characters or concerns. Yet to read Lovecraft is to confront directly that raw Unknown that surrounds us, that is us. To get a healthy dose of perspective: a shambling, roaring, behemoth upswell of perspective.

I mentioned earlier that I think such a perspective can be ultimately nourishing. In an era of economic, cultural and political tumult, when millions of Davids the world over shout in fiery voice against the few far-reaching, corrupt Goliaths, there is morbid comfort in knowing that, despite whatever the megalomaniacal egos of sadistic leaders, immoral bankers, or bribe-pocketing politicians might make of themselves, there are impenetrable forces beyond all of them that will cast mocking eyes towards their suited-up, gold-rimmed delusions, if they even care to acknowledge them. Lovecraft, and the general tradition of Weird Fiction, reminds us just how little power the powerful actually wield. After all, Goliath was, what, ten feet tall? When the mountain-sized Cthulu rises once more, those people will be nothing but scrambling ants — along with the rest of us.

You can catch up on the latest from Mike Robinson at his Facebook page.